Learn modern Schema Design strategies in 2025. Discover best practices for creating scalable, efficient data structures that power analytics and AI.

You know that sinking feeling. You’ve built a beautiful data pipeline. The ETL process is a masterpiece of efficiency. But when users try to query the data, everything is slow. Reports time out. Simple questions become week-long investigations. The problem often isn’t the data or the code—it’s the foundation. It’s the schema design.

Think of schema design as the architectural blueprint for your data. A poor blueprint leads to a wobbly, inefficient, and confusing house. A great one creates a sturdy, well-organized home where everyone can find what they need, quickly and easily.

For a data engineer, mastering schema design is not an academic exercise. It’s a core part of your job that directly impacts query performance, cost, and the sanity of your data analysts.

In this guide, we’ll walk through the seven most critical schema design best practices that will transform your data structures from a liability into your greatest asset. Let’s build a rock-solid foundation.

1. Choose the Right Schema Pattern for the Job

Before you write a single CREATE TABLE statement, you must answer a fundamental question: What is this data for? The answer will point you to the optimal schema design pattern.

The Star Schema: The King of Analytics

This is the most important pattern for analytical workloads. Its schema design is built for one thing: making queries fast and intuitive for business intelligence tools.

What it is:

A central fact table surrounded by dimension tables.

- Fact Table: Holds the measurable, numerical events (the “what happened”).

- Example:

sales_amount,quantity_sold,transaction_id.

- Example:

- Dimension Tables: Hold the descriptive attributes (the “who, what, where, when”).

- Example:

customer_name,product_category,store_location,calendar_date.

- Example:

Why this Schema Design Works:

- Simplicity: Analysts can easily understand and query it. They know to start with the fact table and join to dimensions.

- Performance: It’s optimized for large scans and aggregations. Query engines can quickly filter small dimension tables and then rapidly scan the relevant parts of the large fact table.

- Business Logic: It mirrors how business people think—they want to slice measures (facts) by different categories (dimensions).

Real-Life Example:

A fact_sales table connected to dim_customer, dim_product, dim_date, and dim_store. A query to find “total sales of electronics in California last quarter” becomes a simple join between the fact table and three small, filterable dimension tables.

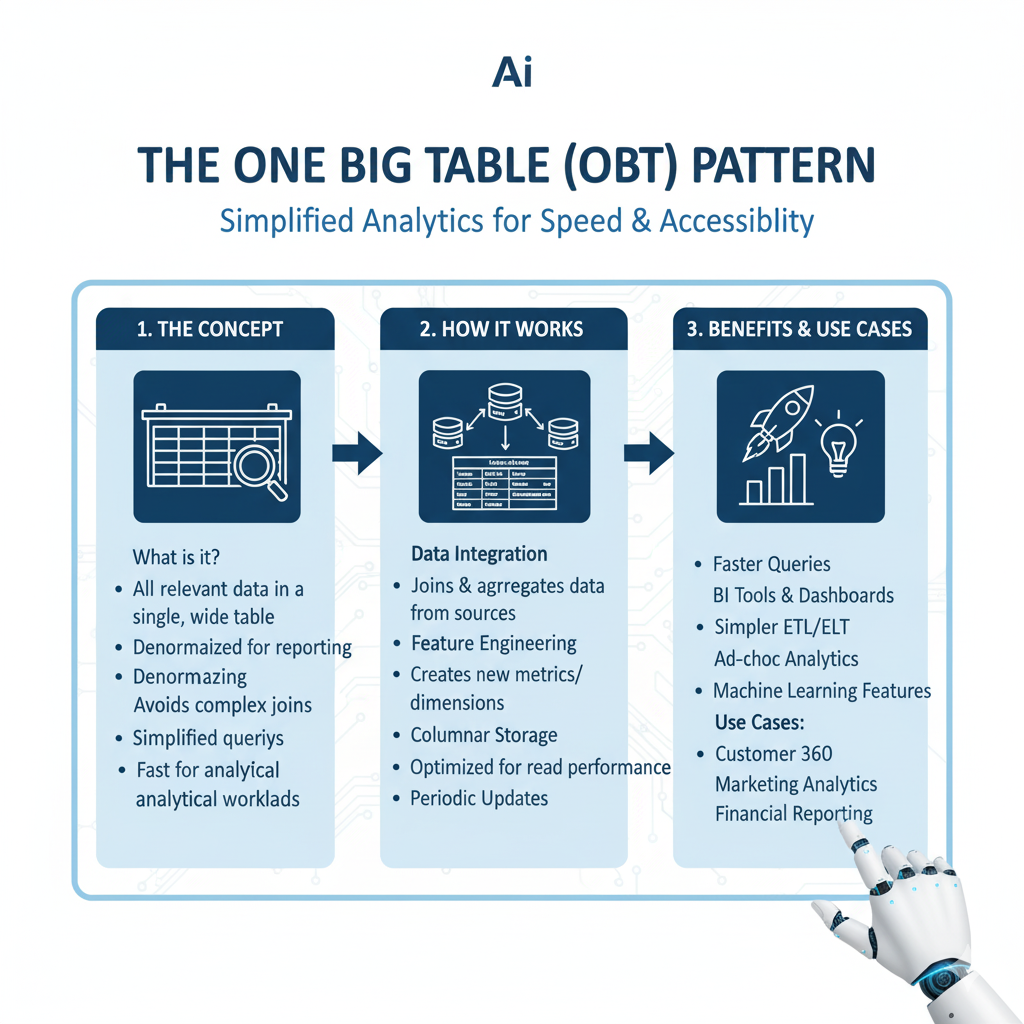

The One Big Table (OBT) Pattern: The Denormalized Workhorse

Sometimes, the cost of joining tables is too high. The One Big Table pattern flattens everything into a single, wide table.

What it is: A fully denormalized table where you pre-join all the dimensional attributes directly into the fact table.

When to Use this Schema Design:

- For Machine Learning: ML models require data in a single, flat file format. An OBT is perfect for feature engineering.

- With Specific Query Engines: Tools like Apache Druid or Presto can perform better with this structure for certain workloads.

- For Extreme Simplicity: When you have a single, well-defined use case and want to avoid any join complexity.

The Major Drawback:

This schema design leads to massive data duplication. A product name might be repeated millions of times in the sales table, wasting storage and making updates a nightmare.

The Verdict: Use the Star Schema as your default. Only use OBT when you have a specific, high-performance need that justifies the trade-offs.

2. Get the Grain Right (The Most Important Step)

The grain of a table is the most fundamental level of detail it contains. Defining the grain is the single most important decision in your schema design process.

What it means: You must be able to complete this sentence with absolute clarity: “One row in this table represents one ______.”

Getting the grain wrong is the root cause of most data quality and accuracy issues.

Examples of Grain:

- “One row in

fact_salesrepresents one line item on a sales receipt.” - “One row in

fact_website_visitsrepresents one user session.” - “One row in

fact_bank_transactionsrepresents one posted transaction.”

A Real-Life Grain Disaster:

Imagine you define the grain of your fact_sales table as “one sale per day.” Later, a business user asks, “What was our best-selling product yesterday?” You can’t answer that! You only have daily totals, not product-level details. Your schema design is flawed because the grain is too coarse.

The Best Practice:

- Design at the Lowest Practical Grain: Capture the most atomic level of detail possible. It is always easier to roll up detailed data into summaries than it is to break down summaries into details.

- State the Grain Explicitly: Document it in your schema design document and in your table’s SQL comments. This prevents confusion for everyone who uses the table later.

3. Use Consistent and Clear Naming Conventions

Your schema design is a form of communication. Consistent naming is the grammar that makes it understandable. A good naming convention is intuitive, predictable, and self-documenting.

Key Rules for a Solid Schema Design Naming Convention:

- Use Snake Case:

fact_sales,dim_customer,customer_first_name. It’s readable and works across all database systems. - Be Consistent with Table Prefixes/Suffixes: Use

dim_for dimension tables andfact_for fact tables. This instantly tells a user what type of table they are looking at. - Use Full, Descriptive Words: Avoid abbreviations.

- Bad:

cust_nm,prod_cat_id,s_amt - Good:

customer_name,product_category_id,sales_amount

- Bad:

- Use Primary Key and Foreign Key Names that Align:

- In your

dim_customertable, the primary key should becustomer_key. - In your

fact_salestable, the foreign key should also be namedcustomer_key.

This makes joins obvious and prevents errors.

- In your

Why It Matters:

When a new analyst joins your team, they should be able to look at your database schema design and, within minutes, understand how to find the data they need. Good naming creates that clarity.

4. Optimize Data Types for Performance and Storage

In schema design, the data types you choose are not just a technical detail. They have a direct impact on storage costs and query speed. Choosing the wrong data type is like using a cargo ship to deliver a pizza—it’s inefficient and expensive.

Best Practices for Data Types:

- Use the Smallest Possible Type: Don’t use

BIGINTifINTwill do. Don’t useVARCHAR(500)ifVARCHAR(50)is sufficient. Smaller data types mean less data to read from disk and move across the network, which means faster queries. - Use Appropriate String Types:

VARCHAR(n)for variable-length text (e.g., names, addresses).CHAR(n)for fixed-length text (e.g., country codes like ‘US’, ‘UK’).TEXTorCLOBfor very long, free-form text, but use these sparingly in analytical tables as they are expensive to scan.

- Be Smart with Dates and Times:

- Use

DATEfor calendar dates. - Use

TIMESTAMPorTIMESTAMPTZ(timestamp with time zone) for precise points in time. Be consistent across your entire schema design.

- Use

- Avoid Using

FLOATfor Exact Numbers: For financial data or anything that requires precise decimals, use theDECIMALorNUMERICtype.FLOATcan introduce small rounding errors.

Real-Life Impact:

A company once stored all IDs as VARCHAR(255). After analyzing their schema design, they switched appropriate IDs to INT. This simple change reduced their storage footprint by 30% and made their most common queries 15% faster due to reduced I/O.

5. Partition and Cluster Your Large Tables

When your fact tables grow to billions of rows, scanning the entire table for every query becomes impossible. This is where partitioning and clustering come in—they are essential schema design techniques for managing massive datasets.

Partitioning: The Big Filter

Partitioning physically divides a large table into smaller, more manageable pieces based on the value of a column.

- Common Partition Key:

date. You might partition afact_salestable bysale_date. Each day (or month) gets its own physical data file. - The Benefit: A query asking for “sales from last week” can automatically prune (ignore) all partitions from other time periods. Instead of scanning 1TB of data, it might only scan 1GB.

Clustering (aka Sort Keys): The Organizer

Within a partition (or the whole table), clustering sorts the data based on one or more columns.

- Common Cluster Key:

product_id,customer_id. - The Benefit: If you frequently filter by

product_id, storing the data in sorted order allows the query engine to quickly locate all rows for a specific product, drastically reducing the amount of data it needs to read.

Schema Design Strategy:

For a fact_sales table, an optimal design would be:

PARTITION BY DATE(sale_date)CLUSTER BY customer_id, product_id

This schema design means a query filtering on a specific date range and a specific customer will be incredibly fast, as the engine only looks at the relevant date partitions and then quickly finds the sorted customer data within them.

6. Document Everything (It’s Not Optional)

The most elegant schema design in the world is useless if no one understands it. Documentation is not a “nice-to-have”; it’s a critical part of the design process.

What to Document in Your Schema Design:

- Table and Column Descriptions: What does this table represent? What does this column actually contain? (e.g., “

customer_lifetime_value– The total net profit attributed to the customer across their entire history, calculated monthly.”) - The Grain: As discussed, state it clearly.

- Data Sources: Where did this data come from? Which pipeline populates this table?

- Refresh Frequency: Is this table updated hourly, daily, monthly?

- Example Queries: Provide one or two common queries to help users get started.

How to Document:

- Use your database’s built-in comment features (

COMMENT ON TABLE fact_sales IS '...'). - Use data catalog tools like DataHub or Amundsen.

- Use a schema design tool like dbt (data build tool), which makes documentation a first-class citizen and can automatically generate a data documentation website.

7. Plan for Evolution with Schema Migration

Your business will change. Your schema design must be able to change with it. A rigid schema that can’t adapt will become a bottleneck. You need a strategy for schema migration.

What is a Schema Migration?

It’s a structured, version-controlled process for making changes to your database schema. Examples: adding a new column, changing a data type, dropping an unused table.

Best Practices for Safe Schema Migrations:

- Use Version Control: All your schema design changes (SQL

CREATE,ALTERstatements) should be in a version control system like Git. This gives you a history of every change and the ability to roll back. - Make Changes Backward-Compatible:

- Adding a new column? Make it

NULLABLEinitially. This allows your existing pipelines to keep working without failing. - Renaming a column? Don’t just

DROPthe old one.ADDthe new column, backfill it with data, phase out the use of the old column in your code, and then, after a grace period,DROPthe old one.

- Adding a new column? Make it

- Automate the Process: Use a migration tool like Flyway or Liquibase. These tools manage the state of your schema and apply changes in a controlled, repeatable way.

The “How Not to Do It” Example:

A developer directly connects to the production database and runs ALTER TABLE customers DROP COLUMN phone_number;. Immediately, a critical reporting dashboard that still referenced that column crashes. A proper schema design migration process would have prevented this.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What’s the biggest mistake you see in beginner schema design?

The most common mistake is confusing the grain of a table, which leads to double-counting or inability to answer specific questions. The second is over-normalizing analytical tables, forcing users to write overly complex queries with a dozen joins. Always start by asking, “What is the grain?”

Q2: How does schema design differ between OLTP and OLAP systems?

They have opposite goals. OLTP schema design (for transactional systems) prioritizes minimizing redundancy and ensuring fast writes through normalization. OLAP schema design (for analytical systems) prioritizes fast query performance for large reads through deliberate denormalization (like the Star Schema).

Q3: Are these practices relevant for NoSQL databases?

The core principles—like clear naming, planning for grain, and designing for access patterns—are universal. However, the implementation is different. In NoSQL, your schema design is often driven by the specific queries you need to run, leading to heavy denormalization and duplication, which is a accepted trade-off for performance.

Q4: What tools can help me implement these best practices?

- dbt (data build tool): Fantastic for building, documenting, and testing your analytical schema design.

- Liquibase/Flyway: For managing and automating schema migrations.

- ER/Diagramming Tools: Like Lucidchart or Draw.io, for planning your design visually before you build.

Q5: How do we handle schema design for semi-structured data like JSON, especially when the structure isn’t fully known?

This is an increasingly common challenge in modern data stacks. The key is to balance flexibility with performance in your schema design approach.

Start with a Hybrid Approach: Don’t just dump the entire JSON blob into a single column. During the initial schema design phase, identify the core, well-known attributes that you’ll frequently filter or group by. Extract these into dedicated, strongly-typed columns. For example, if you’re storing e-commerce events, pull out user_id, event_timestamp, and product_id as separate columns.

Keep the Raw Payload, But Strategically: Store the complete JSON object in a VARIANT or JSONB column (depending on your database). This preserves the raw data for future needs and captures any unexpected fields. However, document clearly that this is a “flexible” zone and that queries against it will be slower. The core of your schema design should still rely on the structured columns for performance-critical operations.

Progressively Structure: As certain JSON fields prove their business value through repeated querying, formally promote them to dedicated columns in a future schema design migration. This iterative process allows your schema to evolve naturally with your business requirements, maintaining both the agility to handle new data and the performance needed for production analytics.

Q6: What’s the role of data types and constraints in ensuring data quality at the schema design level?

Think of data types and constraints as your first and most important line of defense against bad data. A robust schema design uses them not just for storage efficiency, but as active governance tools.

Data Types Enforce Basic Validity: Choosing the correct data type is a fundamental quality check. By defining a column as INT, you prevent alphabet characters from ever entering it. Using DATE or TIMESTAMP ensures temporal values are valid and queryable. Using DECIMAL for financial data, instead of FLOAT, guarantees mathematical precision and prevents subtle rounding errors from corrupting your reports. This proactive schema design choice eliminates entire categories of data cleansing issues downstream.

Constraints Define Business Rules: Beyond basic types, SQL constraints allow you to encode specific business logic directly into your schema design. A NOT NULL constraint ensures a critical field like customer_id is always populated. A CHECK constraint can validate that a discount_percentage column only contains values between 0 and 100. A UNIQUE constraint can prevent duplicate record IDs. When you define a foreign key constraint, you are guaranteeing that every product_id in your fact_sales table has a corresponding entry in your dim_product table, enforcing referential integrity. By catching violations at the point of ingestion, this aspect of schema design prevents inconsistent and untrustworthy data from ever polluting your analytical environment.

Conclusion: Build to Last

Great schema design is an investment. It requires thought and discipline upfront, but it pays massive dividends every single day thereafter. It is the silent force that enables scalable performance, accurate analytics, and a collaborative data culture.

Remember, you are not just building tables. You are building the foundation upon which your entire company makes decisions. You are creating a system that should be understandable, reliable, and adaptable for years to come.

So, the next time you start a new project, don’t just dive in. Take a breath. Think about the patterns, define the grain, choose your names wisely, and document your decisions. Your future self—and every data analyst who ever works with you—will be profoundly grateful.