Introduction: Beyond the “More is Better” Paradigm

The dawn of the big data era was heralded by a powerful, seemingly unassailable mantra: “more data is better data.” For years, the primary challenge and competitive advantage for organizations lay in their ability to collect, store, and process vast, ever-expanding datasets. The promise was that by analyzing the complete population of data—the “N=all” ideal—we could eliminate uncertainty, uncover subtle patterns, and build near-oracular machine learning (ML) models. However, as we stand in 2025, a more nuanced reality has taken hold. The brute-force approach of throwing entire datasets at computational problems is increasingly being recognized as inefficient, costly, and often unnecessary.

In this new landscape, the ancient statistical practice of sampling has been resurrected and reinvented, transforming from a necessary compromise into a sophisticated, strategic tool. Sampling is no longer just about dealing with computational constraints; it is about enhancing model performance, ensuring fairness, accelerating innovation, and making the entire ML lifecycle more agile and sustainable. This article delves into the critical, multifaceted role of sampling in modern big data and machine learning, exploring its theoretical foundations, its practical applications across the ML pipeline, and the advanced techniques defining its use in 2025.

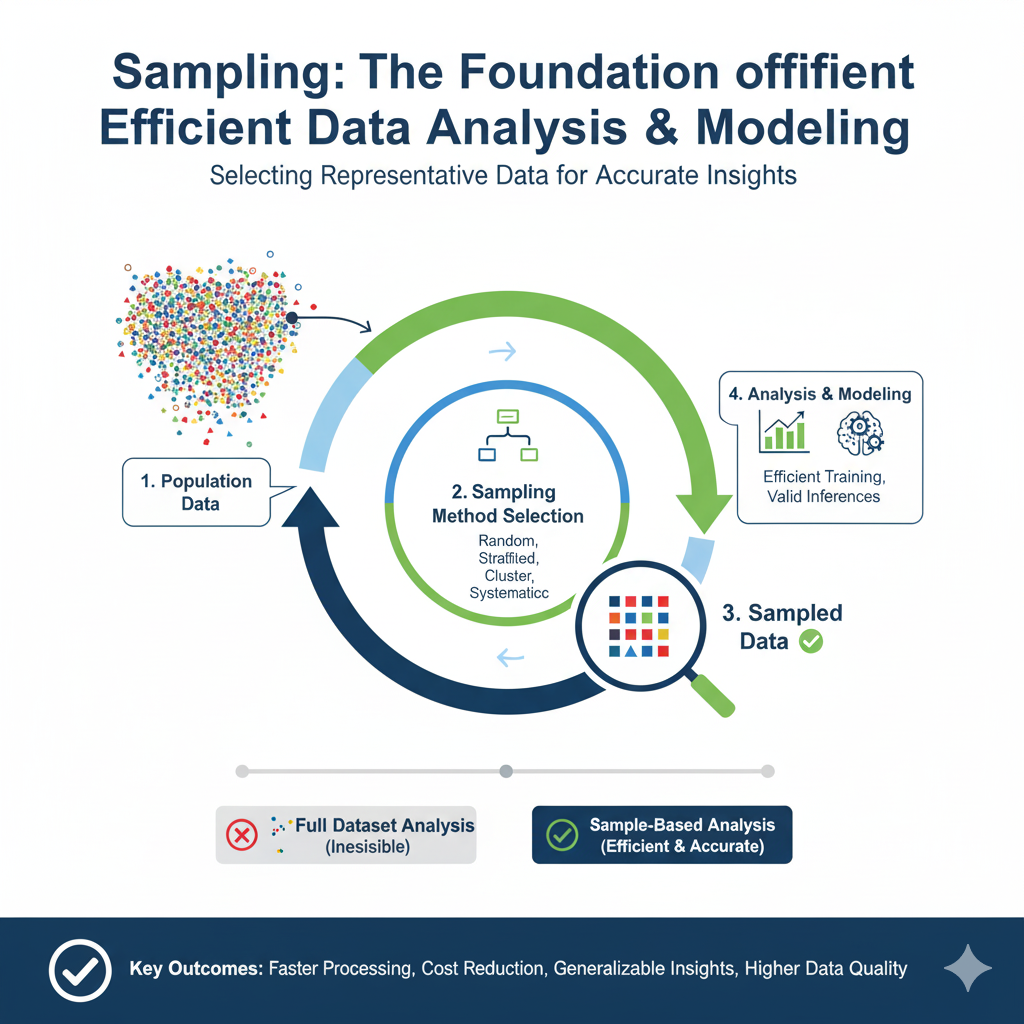

Part 1: The Foundational Bridge – Why Sampling is More Relevant Than Ever

At its core, sampling is the process of selecting a subset of individuals, observations, or data points from a larger statistical population to estimate characteristics of the whole population. While the concept is centuries old, its application in the context of petabyte-scale datasets and complex ML models requires a fresh perspective.

1.1 The Computational Imperative

Despite advances in distributed computing frameworks like Apache Spark and Dask, and the availability of powerful cloud GPUs, processing entire massive datasets remains a significant bottleneck.

- Training Time: Model training time often increases super-linearly with data size. Sampling a representative subset can reduce training time from days to hours or even minutes, enabling rapid prototyping and iterative model development. This agility is crucial in fast-paced business environments.

- Resource Cost: Cloud computing costs are directly tied to processing power and storage. Training on a carefully constructed sample can reduce computational costs by orders of magnitude, making ML projects more economically viable, especially for startups and research institutions.

- Hardware Limitations: Even the most advanced hardware has memory (RAM) limits. Sampling allows data scientists to work with data that fits into memory, facilitating the use of powerful in-memory libraries and algorithms.

1.2 The Statistical and Performance Paradox

Counterintuitively, more data can sometimes lead to worse model performance. This paradox arises from several factors:

- Data Quality and Noise: Large datasets are rarely pristine. They often contain mislabeled examples, outliers, and irrelevant noise. A blind “all-data” approach forces the model to learn these imperfections, leading to poor generalization. Strategic sampling can filter out noise and focus the model’s learning capacity on high-quality, informative examples.

- The Law of Diminishing Returns: For a given model complexity, the performance gains from additional data eventually plateau. After a certain point, adding a million more records may yield a negligible improvement in accuracy. Identifying this inflection point through progressive sampling allows teams to allocate resources efficiently.

- Concept Drift and Relevance: In dynamic systems (e.g., financial markets, social media trends), the underlying patterns in data change over time. A model trained on five-year-old data may be less effective than one trained on a well-sampled, recent subset that accurately reflects the current state of the world.

1.3 The Agile Development Cycle

The modern ML workflow, influenced by MLOps (ML Operations), emphasizes continuous integration, delivery, and training (CI/CD/CT). Sampling is a key enabler of this agility.

- Rapid Experimentation: Data scientists can test dozens of hypotheses, algorithms, and feature engineering strategies on a sample before committing to a full-scale training run. This fail-fast, learn-quickly approach dramatically accelerates the R&D cycle.

- Debugging and Interpretability: Debugging a model trained on billions of records is a nightmare. A smaller, representative sample makes it feasible to analyze errors, understand model behavior, and generate explanations using techniques like SHAP or LIME.

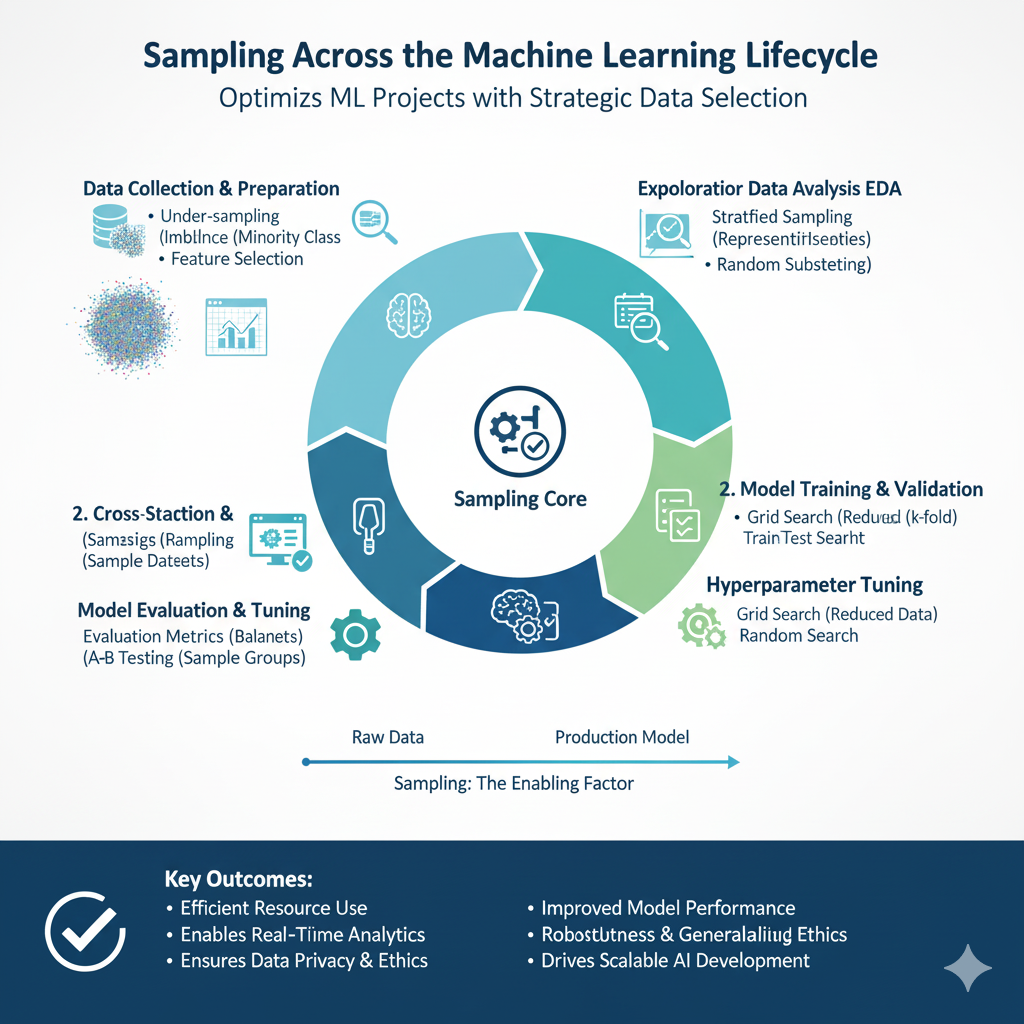

Part 2: Sampling Across the Machine Learning Lifecycle

The application of sampling is not a one-time event but a continuous process that permeates every stage of the ML pipeline.

2.1 Data Preprocessing and Exploration (EDA)

\

Before a single model is built, data must be understood. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) on a massive dataset is impractical.

- Simple Random Sampling (SRS): The most straightforward method, where each record has an equal probability of being selected. It provides an unbiased starting point for initial data profiling, visualization, and quality assessment.

- Stratified Sampling: For EDA, this ensures that the sample contains proportional representation from all important subgroups (strata) within the data. For example, when exploring customer data, you might stratify by geographic region, age group, or product category to ensure all are visible in initial charts and summary statistics.

2.2 Model Training: The Core of Learning

This is where sampling has the most profound impact. The choice of technique here is directly tied to the learning algorithm and the problem context.

- Simple Random Sampling: Still useful for creating initial train/validation/test splits, especially when the data is believed to be homogenous and Independent and Identically Distributed (IID).

- Stratified Sampling for Splitting: When creating training and test sets for a classification problem, it is crucial to maintain the original class distribution in each split. Stratified sampling ensures that a rare class is not accidentally omitted from the training set, which would prevent the model from learning it.

- Resampling for Imbalanced Datasets: Class imbalance is a common plague in ML (e.g., fraud detection, disease diagnosis). Here, sampling techniques are used not to reduce data size, but to rebalance it.

- Oversampling: Increasing the number of instances in the minority class. Techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) create synthetic examples rather than simply duplicating existing ones, leading to more robust models.

- Undersampling: Randomly removing instances from the majority class. This is simpler but risks discarding potentially useful information.

- Mini-Batch Sampling: The workhorse of deep learning. Instead of using the entire dataset (batch gradient descent) or a single sample (stochastic gradient descent) for each weight update, algorithms use a small, randomly sampled “mini-batch.” This provides a sweet spot between computational efficiency and stable, convergent learning.

2.3 Model Evaluation and Validation

A model’s performance must be estimated on data it has never seen. Sampling is foundational to robust evaluation.

- Hold-Out Method: A simple random sample is held out from the training process to serve as a final test set.

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: This gold-standard technique relies entirely on sampling. The dataset is randomly partitioned into K equal-sized folds. The model is trained K times, each time using K-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for validation. This process ensures that every data point is used for both training and validation, providing a more reliable estimate of model performance and reducing the variance of the estimate.

2.4 Inference and Deployment

Even after a model is deployed, sampling plays a role.

- Shadow Deployment: Before a new model replaces an old one, it can be run in parallel on a sampled subset of live traffic. Its decisions are logged and compared to the legacy model’s without affecting actual users, allowing for a final, real-world validation.

- A/B Testing: The quintessential application of sampling in production. User traffic is randomly sampled into control (A) and treatment (B) groups to rigorously test the impact of a new model versus an existing one on key business metrics.

Part 3: Advanced Sampling Techniques Defining the 2025 Landscape

The state of the art has moved far beyond simple random and stratified methods. Advanced sampling techniques are now algorithmic and adaptive, often tightly integrated with the model training process itself.

3.1 Active Learning

Active learning is a paradigm-shifting approach where the learning algorithm itself proactively chooses the data from which it learns. Instead of learning from a static, randomly sampled dataset, the model iteratively queries an “oracle” (usually a human annotator) to label the most informative data points.

- How it works:

- Train an initial model on a small, randomly sampled labeled dataset.

- Use the model to predict on a large pool of unlabeled data.

- Based on a “query strategy,” select the most valuable unlabeled instances (e.g., the ones the model is most uncertain about).

- Send these selected instances to the oracle for labeling.

- Retrain the model with the newly labeled data.

- Repeat from step 2.

- Query Strategies:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Query the instances where the model’s prediction probability is lowest (e.g., closest to 0.5 in binary classification).

- Query-by-Committee: Maintain multiple models (a committee). Query the instances where the committee disagrees the most.

- Expected Model Change: Query the instances that would cause the greatest change to the current model if their labels were known.

- Impact in 2025: Active learning is revolutionizing fields where data is abundant but labels are expensive or time-consuming to acquire, such as medical image analysis, scientific discovery, and document classification. It represents the ultimate form of intelligent sampling, dramatically reducing annotation costs while building highly accurate models.

3.2 Core-Set Selection

The goal of core-set selection is to find a small subset (a “core-set”) of a large dataset such that a model trained on this subset performs nearly as well as a model trained on the full dataset. It frames sampling as an optimization problem.

- How it works: Core-set methods typically use geometric or probabilistic principles to select a set of points that best represent the data distribution of the entire set. One common approach is to select points that form a covering of the data space, ensuring that no data point in the full set is too far from a point in the core-set.

- Techniques: Methods like k-Center Greedy and others based on computational geometry are used to identify these representative points.

- Impact in 2025: This is particularly powerful for deep learning, where it can identify a small fraction of training images that are sufficient for training a model to 90%+ of its full-data accuracy. This is a massive boon for research and development, allowing for ultra-fast experimentation cycles.

3.3 Sampling for Federated Learning

Federated Learning (FL) is a distributed ML approach where model training is performed across a massive number of decentralized edge devices (e.g., smartphones, IoT sensors) without centralizing the raw data. Sampling occurs at two critical levels in FL.

- Client Sampling: In each training round, the central server does not communicate with all clients (which could be millions). Instead, it samples a small subset of available clients to participate in that round. This is essential for managing server load and communication bandwidth.

- On-Device Data Sampling: The data on each client is non-IID and highly personalized. Furthermore, devices have limited computational resources. Therefore, the local training process on each device often relies on sampling from the device’s local dataset to perform efficient SGD updates.

This two-tiered sampling process makes FL feasible, scalable, and privacy-preserving, and it is a key area of research as FL adoption grows.

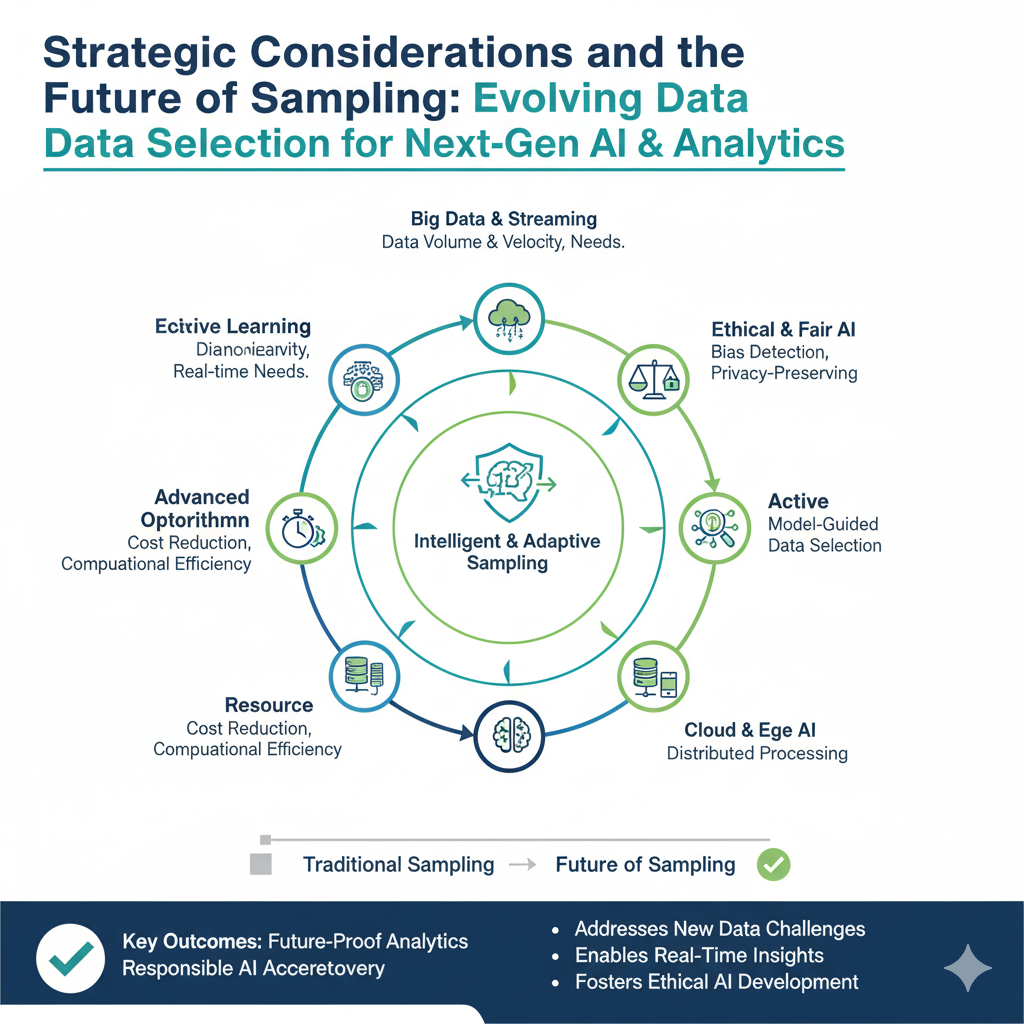

Part 4: Strategic Considerations and the Future of Sampling

Implementing sampling effectively is not without its challenges and requires careful strategic thought.

4.1 Challenges and Pitfalls

- Bias Propagation: If the original dataset is biased, a sample will inherit and potentially amplify that bias. For example, if a historical hiring dataset is biased against a certain demographic, a model trained on a random sample of that data will perpetuate the discrimination. Careful, auditable sampling strategies are required to detect and mitigate this.

- The Curse of Dimensionality: In very high-dimensional spaces (with many features), traditional distance-based sampling methods can break down. The concept of “closeness” becomes meaningless, making it difficult to define a representative sample. This necessitates dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA, UMAP) before sampling or the use of specialized high-dimensional methods.

- Sampling from Data Streams: For applications like network monitoring or financial trading, data arrives as a continuous, unbounded stream. Sampling here requires specialized algorithms like Reservoir Sampling, which can maintain a representative sample of a stream of unknown length.

4.2 The Path Forward: Emerging Trends (2025 and Beyond)

- Ethical AI and Fairness-Aware Sampling: Sampling will be increasingly used as a proactive tool for building fairer AI systems. Techniques are being developed to create samples that are not just representative of the overall population, but that explicitly balance representation across protected attributes (race, gender, etc.), helping to debias training data.

- Integration with MLOps: Sampling pipelines will become first-class citizens in MLOps platforms. Automated systems will monitor data drift and trigger re-sampling and retraining processes when the live data distribution diverges significantly from the sample used for training.

- AI-Generated Synthetic Data: This represents the logical extreme of sampling. Instead of sampling from real data, powerful generative models (like GANs and Diffusion Models) are used to create entirely synthetic datasets that preserve the statistical properties and relationships of the original data while containing no real user information. This solves major problems around data privacy (e.g., GDPR, CCPA) and data scarcity. In 2025, we are seeing a significant rise in the use of high-quality synthetic data for training and testing models in sensitive domains like healthcare and finance.

- Quantum-Enhanced Sampling: While still in its infancy, research is exploring how quantum algorithms could solve complex optimization problems related to core-set selection and other advanced sampling techniques far more efficiently than classical computers, potentially unlocking new frontiers in data selection.

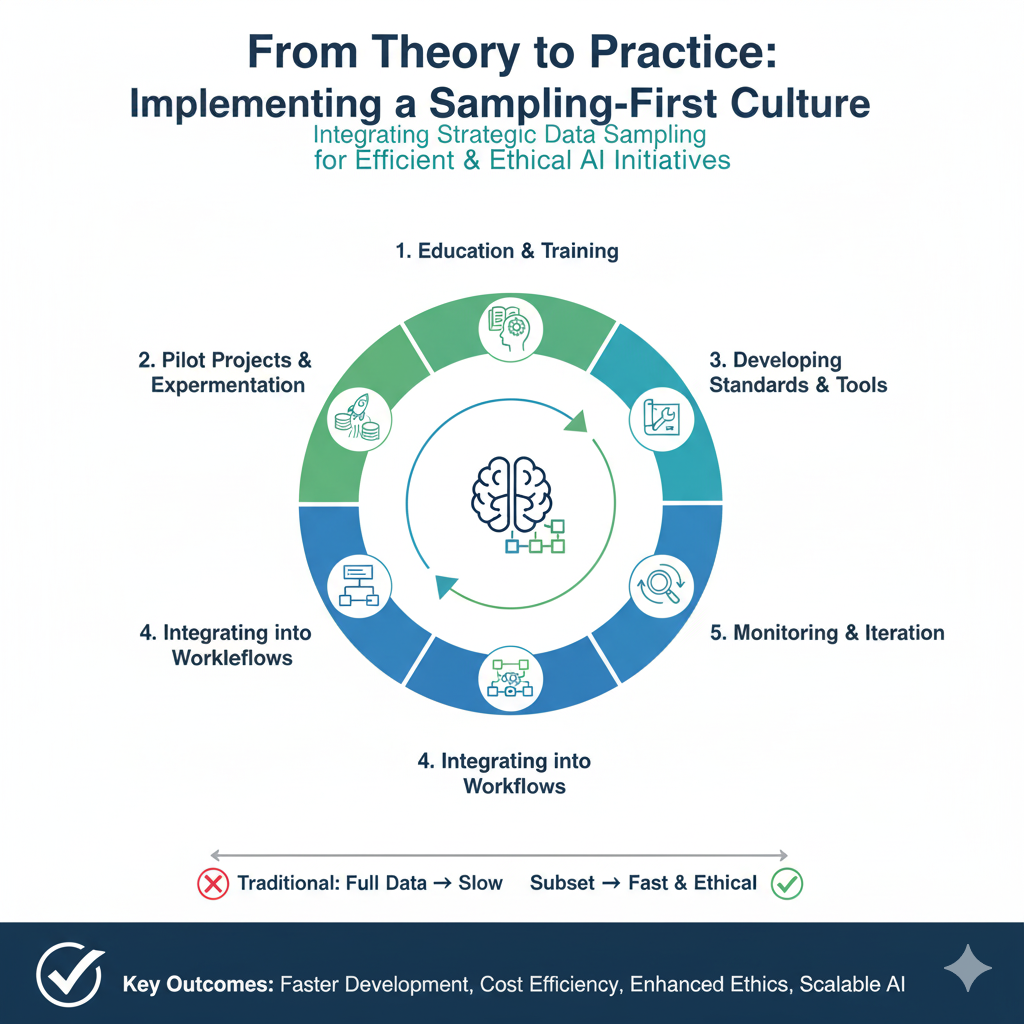

Part 5: From Theory to Practice: Implementing a Sampling-First Culture in 2025

Understanding the “why” and “what” of advanced sampling is only half the battle. The final, critical piece is the “how.” As we move deeper into 2025, the organizations deriving the most value from their data are those that have moved beyond ad-hoc sampling and have embedded it as a disciplined, systematic practice throughout their AI/ML operations. This involves navigating implementation hurdles, managing human factors, and adopting a new philosophical stance toward data.

5.1 Building the Sampling Pipeline: A Practical Framework

Implementing a robust sampling strategy is not a single action but the creation of a reusable, automated pipeline. This pipeline must be as integral to the MLOps stack as the model training and deployment pipelines.

- Step 1: Profiling and Stratification Key Identification: Before any sample is drawn, a comprehensive data profiling process must run automatically on any new dataset. This profile should identify:

- Basic Statistics: Mean, median, standard deviation, missing value rates for numerical features.

- Distribution Shapes: For categorical features, the frequency of each class.

- Correlation and Covariance: To understand relationships between features.

- Recommended Strata: Based on the profiling, the system should suggest potential stratification keys (e.g., “the

countryfeature has 15 values, with ‘Other’ representing 40% of data; stratification is recommended”).

- Step 2: Configurable Sampler Modules: Instead of writing new sampling code for every project, teams should maintain a library of well-tested, versioned “sampler” modules. These could include:

RandomSampler(config: {sample_fraction: 0.1, seed: 42})StratifiedSampler(config: {strata: ['country', 'age_group']})ActiveLearningSampler(config: {query_strategy: 'uncertainty', model: current_model, pool_data: unlabeled_data})ImbalanceResolver(config: {method: 'SMOTE', sampling_strategy: 'auto'})

- Step 3: Automated Validation and Bias Detection: The output of the sampling pipeline must be automatically validated. This involves:

- Distribution Comparison: Using statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov for continuous, Chi-square for categorical) to ensure the sample’s distribution does not significantly diverge from the population’s for key features.

- Bias Audits: Checking the representation of protected attributes (gender, race) in the sample versus the population. Any significant under-representation should trigger a warning or automatically reconfigure the sampler to use fairness-aware methods.

- Step 4: Metadata and Lineage Tracking: Every dataset used for training must be accompanied by immutable metadata that answers critical questions:

- What was the source population? (e.g.,

user_logs_2024) - Which sampler was used, with what configuration? (e.g.,

StratifiedSampler_v1.2 on ['country']) - What is the sample’s fingerprint? (e.g., a hash of the IDs included in the sample).

This level of lineage is non-negotiable for reproducibility, debugging, and compliance.

- What was the source population? (e.g.,

5.2 The Human Factor: Cultivating Sampling Intuition

Technology is only an enabler. The true differentiator is the cultivation of sampling intuition within data teams.

- Shifting the Mindset from “FOMO” to “JOMO”: A common psychological barrier is the “Fear Of Missing Out”—the anxiety that a critical signal lies in the data excluded by the sample. Successful teams cultivate the “Joy Of Missing Out” (JOMO): the confidence that a well-designed sample contains the necessary and sufficient information for the task at hand, leading to faster, cheaper, and often better outcomes.

- The Art of Asking “What is the Question?”: The choice of sampling method is dictated by the business question. Teams must be trained to ask:

- “Are we exploring or confirming?”

- “Is our goal speed or maximum possible accuracy?”

- “Is the phenomenon we’re studying rare or common?”

- “Is the data stream static or dynamic?”

The answers to these questions directly point to the appropriate sampling strategy, making the process less of a black art and more of a disciplined inquiry.

- Cross-Functional Communication: Data scientists must be able to explain their sampling choices to non-technical stakeholders. Being able to articulate, “We used a technique called active learning to focus our labeling budget on the 1% of customer emails that are most ambiguous, which is why our model improved so rapidly,” builds trust and secures buy-in for sophisticated approaches.

5.3 The Economic and Environmental Imperative of Sampling

In 2025, the conversation around AI has expanded to include its total cost of ownership and its environmental footprint. Sampling is a primary lever for managing both.

- The Carbon Cost of Model Training: Training large models, particularly large language models (LLMs), is computationally intensive and has a significant carbon footprint. A study that might require 100 GPU-hours on a full dataset might require only 5 GPU-hours on a well-constructed core-set. By reducing computational demands, strategic sampling directly contributes to Green AI initiatives, making ML research and application more sustainable.

- Cost-Benefit Analysis at Scale: For an enterprise, the decision to train a model on 1 TB vs. 100 GB of data is not just technical; it’s financial. The cost includes cloud compute, data storage, data engineering time, and the opportunity cost of a slower development cycle. A sampling-first approach forces a rational cost-benefit analysis: Will the marginal improvement in model accuracy from the additional 900 GB of data justify its marginal cost? In the vast majority of real-world business problems, the answer is a resounding “no.”

Conclusion: The Master Key to Efficient and Intelligent Machine Learning

The journey of sampling in data science has come full circle. From a humble statistical technique born of necessity, it was temporarily overshadowed by the big data hype, only to re-emerge as a cornerstone of modern, practical, and intelligent machine learning. In 2025, sampling is not about cutting corners; it is about focusing effort. It is the discipline that separates inefficient, brute-force computation from agile, insightful, and sustainable AI.

The most successful organizations and data scientists of this era will be those who master the art and science of sampling. They will understand that the true power lies not in having all the data, but in knowing precisely which data to use, and when. They will wield active learning to minimize labeling costs, employ core-set methods to accelerate research, leverage strategic sampling to ensure model fairness, and harness synthetic data to navigate the complex landscape of privacy. In the age of information abundance, the ability to intelligently select—to sample—is, and will remain, the master key to unlocking the true value of data.