In 2025, AI is more than big data—it’s applied mathematics. Learn how Linear Algebra and Calculus form the core of every AI model, from the structure of neural networks to the learning process itself. Your essential guide to the math behind the magic

Introduction: The Silent Symphony of Mathematics

In the popular imagination, the explosive growth of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Data Science is a tale of algorithms—of neural networks that dream and models that predict the future. We envision lines of Python code, sprawling datasets, and powerful GPUs. While these are the visible actors on the stage, the true directors, the unsung heroes orchestrating this technological revolution, are the centuries-old disciplines of Linear Algebra and Calculus.

As we navigate the complex AI landscape of 2025 for Linear Algebra and Calculus, the reliance on these mathematical foundations has not diminished; it has intensified. The “black box” metaphor for AI is increasingly seen as an oversimplification. To build robust, efficient, interpretable, and groundbreaking AI systems, a profound understanding of the underlying mathematics is no longer a luxury for a few researchers; it is a fundamental prerequisite for practitioners.

This article delves deep into the symbiotic relationship between Linear Algebra and Calculus and modern AI, moving beyond abstract theory to demonstrate their concrete, indispensable roles in the algorithms that are shaping our world. We will explore how vectors and matrices form the very language of data, how derivatives and gradients power the learning process itself, and how these fields are converging to tackle the next frontier: AI reasoning.

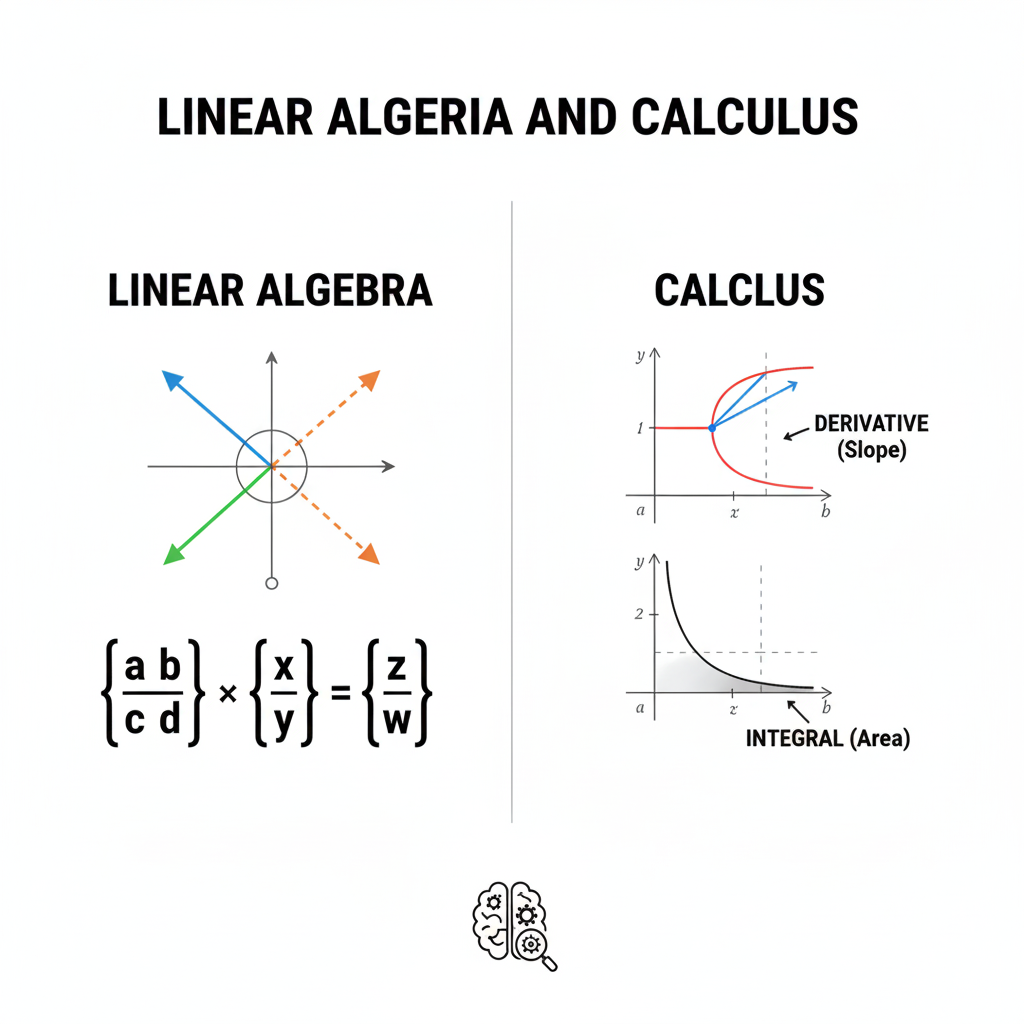

Part I: Linear Algebra – The Architecture of Data and Models

Linear algebra provides the structural and linguistic framework for all computational processes. In the realm of AI and data science, data is not just numbers in a spreadsheet; it is a geometric entity existing in high-dimensional spaces. Linear Algebra and Calculus provide the tools to navigate, manipulate, and extract meaning from this geometry.

1.1 Vectors and Matrices: The Atoms and Molecules of Data

At its core, linear algebra is the study of vectors and matrices.

- Vectors as Data Points: A vector is an ordered list of numbers. In 2025, every piece of data is conceptualized as a vector. A customer’s profile might be a vector

[age, annual_income, purchase_frequency, avg_cart_value]. A word in a document can be represented as a high-dimensional vector (a word embedding) like[0.21, -0.45, 0.87, ..., 0.02]where each dimension captures a semantic or syntactic attribute (e.g., gender, formality, topic). An image is a vector of pixel intensity values. This “vectorization” of the world is the fundamental first step in making data amenable to computation. - Matrices as Datasets and Transformations: A matrix is a 2D array of numbers. It is the natural structure for representing an entire dataset. Each row is a data point (a vector), and each column is a feature. A

1,000,000 x 50matrix perfectly represents one million customers, each described by fifty features.

But matrices are more than just containers. They represent linear transformations—functions that rotate, scale, shear, or project data. This is their true power. Applying a matrix to a vector transforms it, moving it to a new location in its vector space.

1.2 Key Operations and Their AI Manifestations

The operations of Linear Algebra and Calculus are the verbs and sentences of this data language.

- Dot Product and Cosine Similarity: The dot product of two vectors measures their alignment. A high dot product indicates the vectors are pointing in a similar direction. This is the engine behind:

- Recommendation Systems: To recommend a product to a user, a system computes the dot product between the user’s preference vector and the product’s attribute vector. A high score triggers a recommendation.

- Semantic Search: Modern search doesn’t just match keywords; it finds meaning. By representing queries and documents as vectors, the cosine similarity (a normalized dot product) can find documents that are semantically similar to a query, even if they share no common words.

- Matrix Multiplication: The Composition of Transformations: This is the workhorse of deep learning. A neural network layer is essentially a matrix. The input data (a vector) is passed through this matrix via multiplication, resulting in a transformed output vector. A deep network is a chain of these matrix multiplications, interleaved with non-linear activation functions. Each layer’s matrix learns to apply a specific transformation, progressively extracting higher-level features—from edges in an image to object parts to entire faces.

- Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues: Unveiling Structure: Eigenvectors of a matrix are the special vectors that do not change their direction when the transformation is applied; they are only scaled by a factor (the eigenvalue). They reveal the fundamental “axes” or “patterns” within the data.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): PCA, a cornerstone of dimensionality reduction, is fundamentally an eigen-decomposition of the covariance matrix. The eigenvectors (principal components) are the directions of maximum variance in the data. By projecting data onto the top few eigenvectors, we can reduce dimensionality while preserving the most important information, crucial for visualization and efficient computation.

- PageRank Algorithm: The core of Google’s original algorithm, PageRank, models the web as a graph, represented by a massive matrix. The eigenvector of this matrix with the largest eigenvalue represents the “importance” of each web page. The entire structure of the modern web is, in a sense, dictated by this eigenvector.

- Matrix Decompositions: The Art of Factorization: Techniques like Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) factorize a matrix into simpler, constituent matrices. SVD is ubiquitous:

- Collaborative Filtering: Used in recommendation systems to factorize a user-item interaction matrix, uncovering latent factors that explain user preferences (e.g., “affinity for sci-fi” or “preference for indie directors”).

- Natural Language Processing (NLP): Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), a precursor to modern word embeddings, uses SVD to find the latent semantic topics in a corpus of text.

1.3 Linear Algebra in 2025: Beyond Fundamentals

The role of Linear Algebra and Calculus is evolving with the frontiers of AI.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): As AI moves towards understanding relational data (social networks, molecular structures, knowledge graphs), GNNs have taken center stage. The core operation in a GNN is message passing, where node features are aggregated from their neighbors. This aggregation is fundamentally a linear algebraic operation on the graph’s adjacency matrix and node feature matrix, allowing models to learn from the structure and features simultaneously.

- Geometric Deep Learning: This field extends the principles of convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—which rely on the convolution operation, a specialized form of matrix multiplication—to non-Euclidean data like manifolds and graphs. It formalizes the notion of symmetry and invariance using group theory, which is deeply rooted in linear algebra.

- Tensor Operations for Multimodal AI: Modern AI systems fuse data from multiple modalities—text, image, audio. The mathematical object for representing such multi-dimensional data is a tensor (a generalization of a matrix to higher dimensions). The training and inference of these complex models rely heavily on tensor operations, a direct extension of linear algebra.

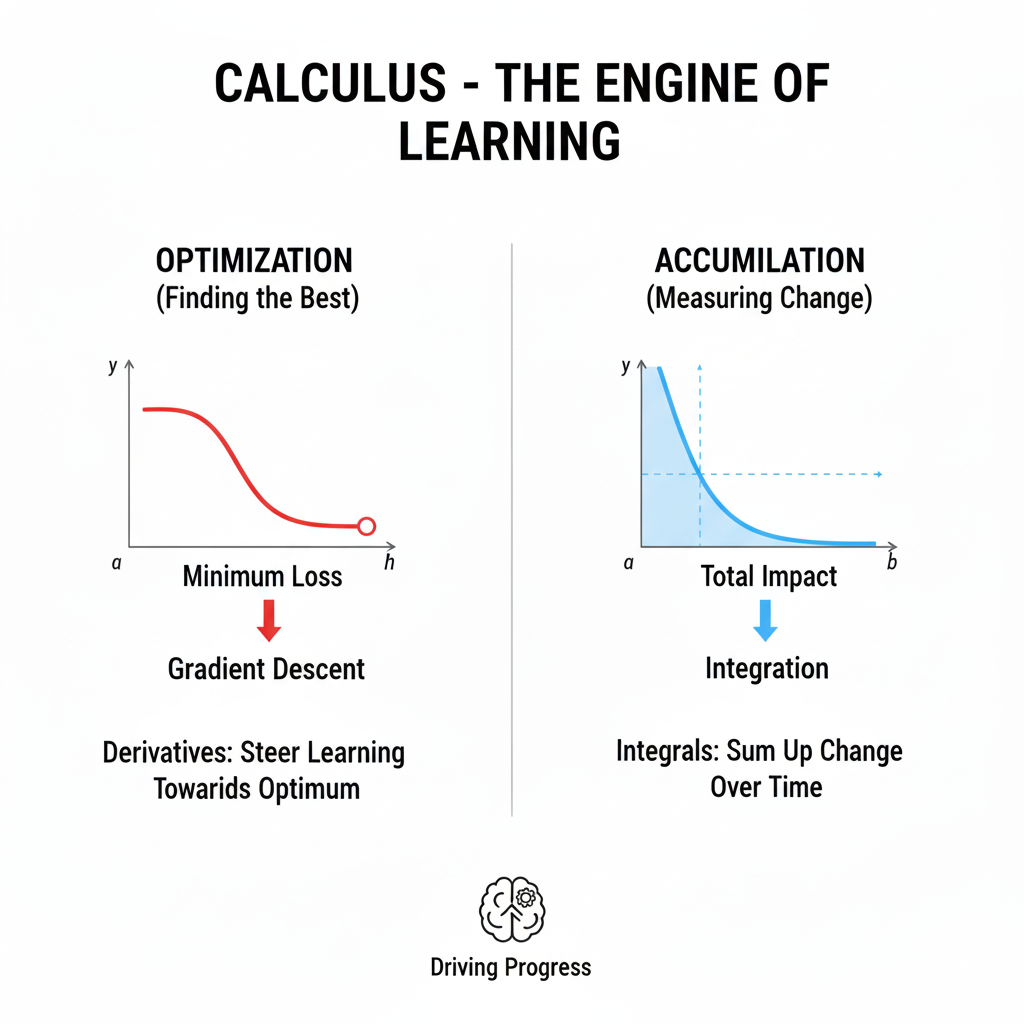

Part II: Calculus – The Engine of Learning

If linear algebra provides the architecture, calculus provides the dynamics. Calculus is the mathematics of change, and learning is fundamentally a process of change—iteratively adjusting a model’s parameters to improve its performance. The bridge between them is the critical concept of optimization, a central pillar where Linear Algebra and Calculus converge.

2.1 The Derivative: Measuring Instantaneous Change

The derivative of a function at a point tells us the slope, or the rate of change, at that point. In the context of a machine learning model, the “function” is the loss function (or cost function). This function measures how badly the model is performing—the error between its predictions and the true values. The “point” is the current set of the model’s parameters (weights and biases, which are often represented as matrices and vectors).

2.2 The Gradient: The Compass in High Dimensions

For a function of multiple variables (like a loss function that depends on millions of model parameters), the derivative generalizes to the gradient. The gradient (denoted ∇) is a vector of partial derivatives. It points in the direction of the steepest ascent of the function. If we want to minimize the loss, we need to move in the opposite direction: the direction of the steepest descent.

2.3 Gradient Descent: The Fundamental Algorithm of AI

This simple, powerful idea is the foundation of almost all machine learning. The algorithm is as follows:

- Initialize: Start with random values for the model’s parameters (let’s call this vector w).

- Forward Pass: Pass data through the model to compute the loss,

L(**w**). - Backward Pass (Backpropagation): This is where calculus shines. Using the chain rule from calculus, compute the gradient of the loss with respect to every parameter,

∇L(**w**). Backpropagation is an efficient, dynamic programming-like application of the chain rule through the computational graph of the neural network. - Update: Nudge the parameters a small step in the negative direction of the gradient:

**w** = **w** - η * ∇L(**w**)

Here,ηis the learning rate, a hyperparameter that controls the size of the step. - Repeat: Iterate steps 2-4 until the loss converges to a minimum.

This elegant process, powered by the chain rule, allows a model with millions or even billions of parameters to slowly, incrementally, “learn” the patterns in the data. The entire field of deep learning is built upon this optimization framework.

2.4 Variants and Advanced Optimizers

The basic Gradient Descent has evolved into more sophisticated variants crucial for 2025’s large-scale models:

- Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD): Instead of computing the gradient using the entire dataset (which is computationally prohibitive for large

N), SGD uses a single, randomly chosen data point. This introduces noise but allows for much faster iteration. - Mini-batch Gradient Descent: A compromise that uses a small, random subset (mini-batch) of the data. This is the standard in modern deep learning, offering a balance between computational efficiency and stable convergence.

- Adaptive Optimizers (Adam, AdaGrad, RMSProp): These are the optimizers of choice today. They don’t just use the gradient; they also keep a running average of past gradients and their squares. This allows them to adapt the learning rate for each parameter individually, leading to much faster and more robust convergence. The mathematics behind these involves concepts from momentum and second-order moments, all grounded in Linear Algebra and calculus.

2.5 Calculus in 2025: Refining the Engine

The application of Linear Algebra and Calculus is becoming more nuanced and critical.

- Second-Order Optimization and Physics-Informed AI: While first-order derivatives (the gradient) are standard, second-order derivatives (the Hessian matrix) provide information about the curvature of the loss landscape. Methods that approximate the Hessian can lead to faster convergence. This is particularly relevant in Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), where the model must not only fit data but also obey physical laws described by differential equations (e.g., Navier-Stokes equations for fluid dynamics). Solving these requires computing higher-order derivatives, a process made easy by modern automatic differentiation libraries.

- Adversarial Robustness and Gradient-Based Attacks: The vulnerability of deep learning models to adversarial examples—tiny, carefully crafted perturbations that cause misclassification—is a major security concern. These attacks are often generated using the gradient of the loss with respect to the input image itself, not the model parameters. By calculating which pixels to change to maximize the loss, an attacker can create a “fooling” image. Defending against such attacks also relies on understanding and regularizing these gradients.

- Explainable AI (XAI) and Saliency Maps: To peek inside the “black box,” techniques like Grad-CAM and other saliency methods use gradients. They compute the gradient of a model’s output (e.g., the score for “cat”) with respect to the input image pixels. This generates a heatmap highlighting the pixels most “responsible” for the decision, providing a form of visual explanation Linear Algebra and calculus.

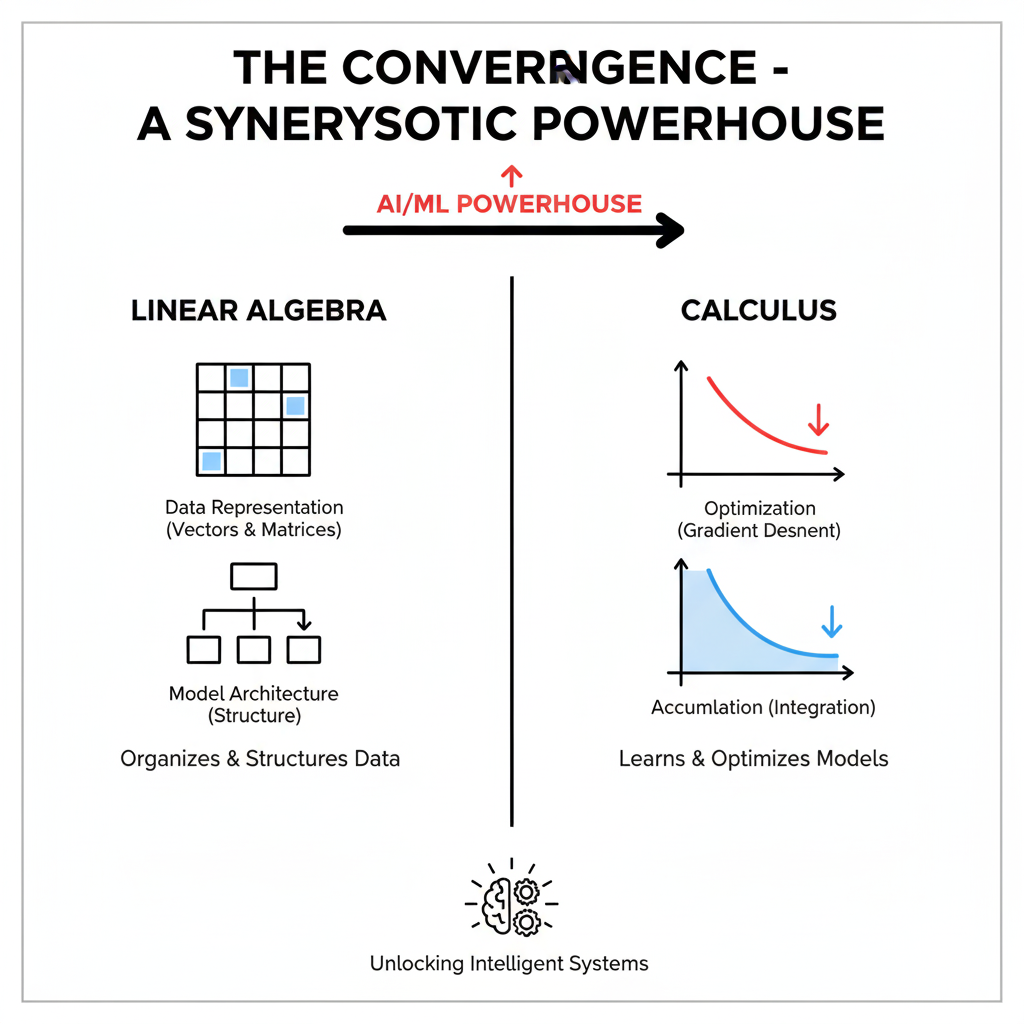

Part III: The Convergence – A Synergistic Powerhouse

Linear Algebra and Calculus are not isolated tools; they are deeply intertwined. Their synergy is most evident in the core computational techniques that underpin modern AI frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch.

3.1 The Computational Graph: A Unified Abstraction

Modern deep learning frameworks represent every model as a computational graph. The nodes are operations (e.g., matrix multiplication, a convolution, a sigmoid function), and the edges are the data (tensors) flowing between them. This abstraction elegantly unifies Linear Algebra and Calculus:

- Forward Pass: Data (tensors) flows through the graph, executing a series of linear algebraic operations (matrix multiplications, etc.) to compute the final output and loss.

- Backward Pass: The framework automatically computes the gradient for every parameter in the graph by traversing it in reverse, applying the chain rule at every node. This process, known as automatic differentiation (AutoDiff), is seamless. The programmer defines the forward pass (the linear algebra), and the framework handles the Linear Algebra and calculus.

3.2 A Concrete Example: Training a Simple Neural Network Layer

Let’s synthesize the concepts. Linear Algebra and Calculus Consider a single layer of a neural network with a linear transformation followed by a ReLU activation function.

- Forward Pass (Linear Algebra):

- Input: Vector x.

- Weights: Matrix W, Bias: Vector b.

- Linear Transformation: z = W * x + b (A matrix-vector multiplication and vector addition).

- Activation: a = max(0, z) (Applies the ReLU function element-wise).

- Loss Calculation:

- Let the true label be y. The loss

Lcould be the mean squared error:L = (1/2) * ||a - y||².

- Let the true label be y. The loss

- Backward Pass (Calculus via the Chain Rule):

To update W and b, we need∂L/∂Wand∂L/∂b.∂L/∂a=a - y∂L/∂z=∂L/∂a * ∂a/∂z. Since ReLU is 1 forz>0and 0 forz<0,∂a/∂zis a diagonal matrix with 1s and 0s. So,∂L/∂zis a masked version of∂L/∂a.∂L/∂W=∂L/∂z * ∂z/∂W=∂L/∂z * xᵀ(This results in a matrix, as expected).∂L/∂b=∂L/∂z(The sum of the gradients flowing into the bias node).

The update step **W** = **W** - η * ∂L/∂W is then a simple linear algebraic operation. The entire learning process is this beautiful dance between the structure of linear algebra and the dynamics of Linear Algebra and calculus.

Part IV: The 2025 Landscape – New Frontiers Demanding Deeper Foundations

As we look at the cutting edge of AI in 2025, the demands on understanding Linear Algebra and Calculus are greater than ever.

4.1 The Era of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Transformers

Models like GPT-4, Claude, and Llama are the pinnacle of this mathematical synergy.

- Linear Algebra: The Transformer architecture is a masterpiece of linear algebra.

- Embeddings: Words are converted into high-dimensional vectors.

- Query, Key, Value Matrices: The self-attention mechanism uses three learned linear transformations (matrices) to project the input embeddings into Queries, Keys, and Values.

- Attention Scores: The attention score between two words is computed as a scaled dot product between the Query vector of one and the Key vector of the other. This is a massive matrix multiplication operation (

Q * Kᵀ). - Feed-Forward Networks: Each layer in the Transformer contains a small neural network, which is again a series of matrix multiplications.

- Calculus: Training a model with hundreds of billions of parameters is the largest-scale optimization problem humanity has ever attempted. It relies entirely on distributed variants of gradient descent. Furthermore, techniques like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), used to align models, involve optimizing a reward model, again using gradient-based methods Linear Algebra and calculus.

4.2 Generative AI and Diffusion Models

The rise of image and video generation models like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion is another testament.

- Linear Algebra: The U-Net architecture at the heart of these models is a convolutional neural network, which relies on convolution operations (a specialized form of cross-correlation, implemented via matrix multiplication with a Toeplitz matrix). The process of gradually adding noise to an image and then training a network to reverse this process is defined through a series of linear transformations Linear Algebra and Calculus.

- Calculus: The sampling process in diffusion models can be interpreted as solving a stochastic differential equation (SDE). Advanced samplers use concepts from numerical methods for SDEs, which are rooted in calculus, to generate higher-quality images faster.

4.3 The Quest for AI Reasoning and the Role of Mathematics

The next frontier is moving from pattern recognition to true reasoning and planning. This is pushing the boundaries into more advanced mathematical territories.

- Differentiable Programming: This paradigm views entire programs, including their control flow (loops, conditionals), as differentiable functions. This allows gradients to be calculated through algorithms that were previously “un-trainable,” enabling systems to learn algorithms and logical rules, bridging the gap between connectionist and symbolic AI.

- Causal Inference: Moving beyond correlation to causation is critical for robust AI. Causal models, often represented as directed acyclic graphs, use a combination of graph theory (a cousin of Linear Algebra and calculus) and probability theory (which relies heavily on calculus for continuous distributions) to model and infer causal relationships .

The 2025 Reality: Beyond the “Big Data” Myth

The early 2010s narrative was seductive: gather a massive dataset, throw immense computational power at it, and watch the AI magic happen. In 2025, we see the limitations of this approach. While scale is a factor, it is not a substitute for intelligence. The true “soul” of AI, as you aptly put it, is the mathematical framework that gives data and compute their purpose and direction. This framework is built upon the twin pillars of Linear Algebra and Calculus.

To dismiss Linear Algebra and Calculus as mere academic formalities is to misunderstand the very fabric of modern AI. They are not in the background; they are the stage and the script. Let’s expand on your powerful metaphors.

Linear Algebra: The Stage and the Scaffolding

Your metaphor of Linear Algebra providing the “stage” is perfect. But in 2025, we must think of it not as a static stage, but as a dynamic, multi-dimensional scaffolding that both holds the data and constructs the model itself.

- The Language of Structure: Every data type has its native structure in Linear Algebra and calculus. An image is a tensor (a multi-dimensional array). A social network is a graph, represented by an adjacency matrix. A sentence is a sequence of word vectors. Linear Algebra provides the grammar to manipulate these structures. A convolutional layer in a vision model uses Linear Algebra (specifically, convolution as a structured matrix multiplication) to respect the spatial hierarchy of pixels. A transformer model uses Linear Algebra (the self-attention mechanism, which is a series of matrix multiplications) to respect the contextual relationships between words. Without Linear Algebra, we have no coherent way to represent or process this structured information.

- The Architecture of the Model Itself: A neural network is, at its core, a stack of linear transformations. Each layer’s weights are a matrix. The act of inference is a forward pass of data through these matrices, with non-linearities in between. The very architecture of the AI is a manifestation of Linear Algebra and calculus. When a model like GPT-4 with hundreds of billions of parameters is loaded into memory, it is, in essence, a massive, interconnected web of matrices and vectors residing in Linear Algebra space. Understanding this is crucial for model design, compression, and efficient deployment.

Calculus: The Dynamic Plot of Learning

If Linear Algebra is the stage, Calculus is the director and the plot, guiding the actors (the model parameters) through a story of continuous improvement. The “plot” is the optimization narrative, and it is driven entirely by gradients.

- The Engine of Gradient Descent: The fundamental algorithm of AI, Gradient Descent, is pure applied Calculus. The loss function is a complex, high-dimensional landscape. The gradient, a concept from Linear Algebra and calculus, is the compass that points uphill. By moving against the gradient (gradient descent), the model finds its way downhill towards a minimum. Every single parameter update in every model, from a simple logistic regression to a massive diffusion model, is a step dictated by Calculus. The learning rate, momentum in optimizers like SGD, and adaptive learning rates in Adam—all these concepts are refinements built upon the foundational principles of Calculus.

- Debugging with Derivatives: When a model fails to learn or produces bizarre outputs, an engineer who only sees a black box is helpless. An engineer versed in Linear Algebra and calculus can investigate the gradients. Are they vanishing (becoming zero) or exploding (becoming impossibly large)? This is the classic vanishing/exploding gradient problem, diagnosed and solved using an understanding of the chain rule from Calculus. Tools like gradient clipping and normalized initialization schemes are direct solutions to problems identified through Calculus.

The Indispensable Synergy in 2025

In 2025, the most exciting advancements are happening at the intersection of these two fields. The synergy between Linear Algebra and Calculus is not just a convenience; it is a computational necessity.

- Automatic Differentiation (AutoDiff): Frameworks like PyTorch and JAX perform magic by leveraging this synergy. The programmer defines the forward pass using the operations of Linear Algebra and calculus (matrix multiplications, convolutions, etc.). The framework then automatically constructs the backward pass to compute gradients using Linear Algebra and calculus. This seamless integration of Linear Algebra and Calculus is what makes rapid prototyping and research possible. You cannot effectively use these tools without an intuitive feel for what they are doing under the hood.

- Advanced Architectures: Consider a Graph Neural Network (GNN) used for drug discovery. The Linear Algebra and calculus is used to represent the molecule as a graph and to perform message-passing operations between atoms. The learning process—how the model adjusts its parameters to better predict molecular properties—is entirely driven by Calculus through backpropagation. The entire training loop is a dance between the graph-based Linear Algebra and the gradient-based Linear Algebra and calculus.

The Clarion Call for Practitioners

This leads to your powerful “clarion call.” The difference between a passenger and a driver in the AI revolution is the depth of their mathematical understanding.

- To Innovate, Not Just Implement: Anyone can call a

model.fit()function in Python. But can you design a novel attention mechanism? Can you create a more efficient optimizer? Can you modify a GNN for a new type of relational data? These breakthroughs require you to manipulate the stage and rewrite the plot—they require a deep, intuitive command of Linear Algebra and Calculus. - To Debug the Invisible: When a model with 50 million parameters fails, you cannot step through it line by line. Your diagnostics are mathematical. You must analyze the distribution of activations (a statistical concept built on Linear Algebra), inspect the gradient flow (a Linear Algebra and calculus concept), and understand the conditioning of the loss landscape (a concept uniting both). This is impossible without this knowledge.

- To Wield Responsibly: In 2025, with AI integrated into critical systems, understanding why a model fails is as important as knowing that it works. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like Saliency Maps and SHAP values are fundamentally based on computing the gradient of the output with respect to the input (Linear Algebra and calculus) and projecting it back onto the data structure (Linear Algebra and calculus). To audit for bias, ensure robustness, and build trustworthy AI, we must be able to peer inside, and that requires the lens of Linear Algebra and Calculus.

Conclusion: The Immutable Backbone

Therefore, the statement that Linear Algebra and Calculus are the “immutable backbone” is not hyperbole; it is a technical reality. As models grow in complexity and are applied to more ambitious problems, the underlying mathematics does not become obsolete; it becomes more critical. New architectures will emerge, new optimization algorithms will be invented, but they will all be expressions and extensions of the fundamental principles of Linear Algebra and Calculus.

For the aspiring AI professional in 2025, investing time in mastering Linear Algebra and Calculus is the highest-leverage activity available. It is the key that unlocks true understanding, empowers genuine innovation, and enables the responsible stewardship of the most transformative technology of our time. The revolution is not just being coded; it is being calculated.